Long Biography

Ancestry and childhood

Robert Casadesus was born into a family of musicians. His grandfather, Luis, a Catalan immigrant, would have liked to be a violinist. As circumstances prevented him from realizing his dream (he was a typographer, then an accountant and, at night, conducted café-concert orchestras), he promised himself that his children would be musicians. Luis and his wife, Mathilde Sénéchal, gave birth to 13 children, nine of whom survived, and eight were musicians.

Amongst them: Robert Casa, Robert’s father, an actor and songwriter, was born in 1878. A member of Sacha Guitry’s company, he was appointed director of the Théâtre français of New York in the 1920s by Charles Dullin. One might say that the birth of Robert (the future pianist) occurred beneath a serene sky. It was in 1899, and his father, then aged 21, had an affair with one of his classmates at the Conservatoire where he was studying diction.

Robert was the fruit of this youthful union. The young woman not wishing to assume the role of motherhood, Robert Senior decided to keep the child rather than see it put up for adoption. The Casadesus clan welcomed the new-born without a shadow of hesitation. The task of taking care of him fell to Aunt Cécile—aged 15. Legally recognized by his father and adopted by the whole family, Robert never knew his mother. The affection of the ‘tribe’ largely compensated for this absence.

His gifts for music manifested themselves at an early age. Luis decided to have him study the violin for, said he: ‘With a violin, one is sure of finding work!’

Robert did not see things that way and soon gave up the violin for the piano, at which he sat with authority and determination. After Aunt Cécile got married, it was Aunt Rosette who took over his upbringing.

Throughout his life, Robert considered Aunt Rosette his mother. She was, moreover, the captain of the Casadesus vessel, and it was she who gave Robert his start at the piano.

Studies and early career

Without further ado, his exceptional gifts were noticed by all who heard him. The great piano teacher of the era, Isidore Philipp, entrusted him, without the slightest hesitation, to his coach so that he might personally make him work according to his methods.

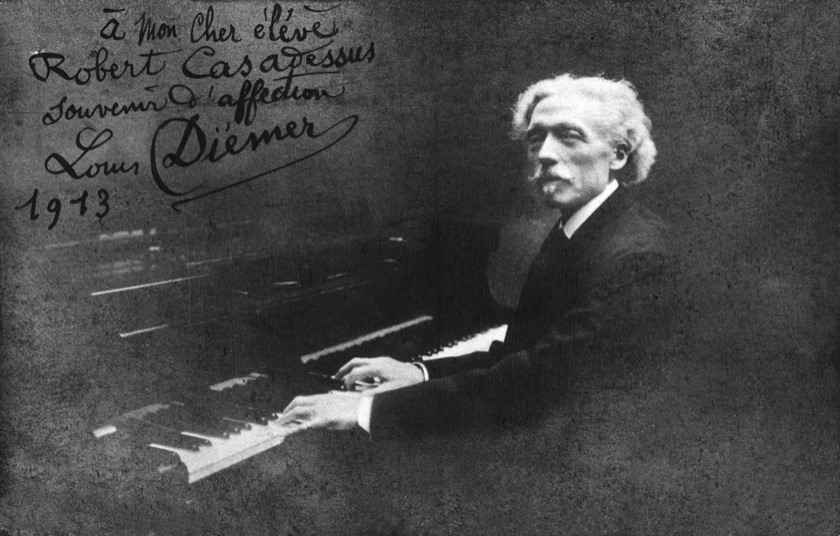

From that time on, young Robert successfully entered one competition after another and obtained his first medal in solfeggio from Lavignac, in 1911 and his First Prize in piano at 14 in the class of Louis Diémer, another renowned professor.

Robert interpreted Gabriel Fauré’s Variations, and the composer, then director of the Paris Conservatoire, was a member of the jury. After his performance, Fauré went up to Robert and, patting him on the check, said: ‘You’ll make a good little pianist’. Robert then entered the class of Lucien Capet, who had an exceptional influence on him.

Lucien Capet had founded a quartet, Le Quatuor Capet, famous at the time, in which two of Robert’s uncles played: Henri and Marcel. The quartet often rehearsed at the Casadesus and this is how Robert was introduced to chamber music. The Beethoven Quartets held no secrets for him. He knew them all by memory without ever having played them!

At that time, Robert was playing in a duet with his uncle Marius, his senior by seven years. Marius, a talented violinist, played in the Ensemble des Instruments Anciens founded by his brother Henri, violist. Thus Robert’s childhood was bathed in music.

Many years later, Marius and Robert would give numerous concerts together. But one of the major events of Robert’s youth was, without any doubt, his meeting, at the Conservatoire in Paris, the young Gabrielle L’Hote, a few years younger than himself and a fellow piano student in Diémer’s class.

Gaby: meeting, marriage, duo

An encounter under the sign of music, certainly, but also the birth of a complicity that would develop intensely and without weakening their whole lives long. After Robert’s death, Gaby, endowed with inexhaustible energy, would long continue to perpetuate the memory of her husband. One might say that Robert & Gaby Casadesus formed a couple exemplary in every way, be it private or professional life. Whereas there might have been a certain rivalry between two artists playing the same instrument, quite the contrary, there grew up between them a fusion, a complementarity such that one might say their two lives evolved as four hands.

In spite of the fact that most of Gaby’s performances were either four hands or two pianos with her husband, several of her performances as a soloist with orchestra in France and in the US were noteworthy, as well as a sizable discography. Her lifelong involvement in teaching, particularly within the context of the Fontainebleau Schools of Music and Fine Arts, was a fundamental aspect of her career as a pianist (see her published method: My Daily Technique). She also devoted much time to a revised publication of some of Ravel’s piano works, having been intimately acquainted, as well as her husband, with the composer and his musical ideas during his lifetime.

The ‘duo-couple’ would endure, moreover, beyond Robert’s death in 1972. Indeed, without ever yielding, Gaby would devote the remainder of her life to maintaining the memory of her husband’s art and, in order to do so, created, a few months after his passing, the ‘Association Robert Casadesus’ with her son, Guy. She founded the Robert Casadesus International Piano Competition in Cleveland, Ohio, which was later to take on a different format with the Rencontres Internationales de Piano de Lille, under the aegis of Jean-Claude Casadesus.

Watching over the renewal of Robert’s recorded repertoire throughout the world, she would also make known her composer-husband’s catalogue, consisting of 69 opus numbers, including seven symphonies, several concertos (for one piano, two and three pianos, violin, cello, flute) and numerous chamber works. She would also found the Cleveland International Piano Competition, later relayed, thanks to Jean-Claude Casadesus, by the International Piano Encounters of Lille.

In 1999, at the end of the celebrations organized for her husband’s centenary, Gaby joined him, surely with the feeling of having done her duty as spouse and partner.

Collaboration with Ravel and the American Conservatory

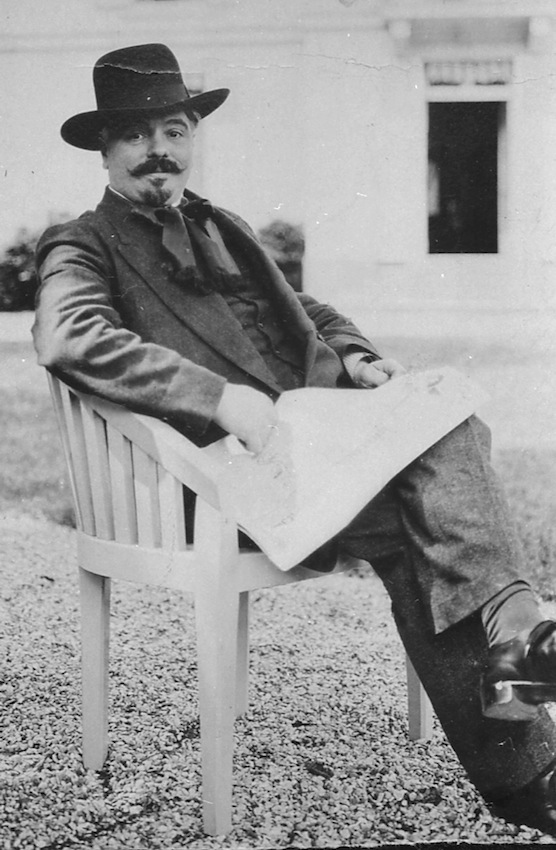

But let us return to the early career of this young pianist couple. Robert embarked on the concert circuit quite naturally. In the 1920s, he worked on Ravel’s music, which he performed in the composer’s presence, and a real friendship developed between the two men. Ravel told him one day after a recital: ‘You must be a composer yourself to play the works of others in such a way!’ Ravel had heard correctly. Robert had always composed and would continue to compose throughout his life.

Ravel played a major part in Robert Casadesus’ life and career: their professional collaboration and their personal friendship lasted over a dozen years, until Ravel died in 1937. Robert and Gaby described for us an unpretentious, straightforward man who hated publicity and giving speeches, to the point that on occasion, he would ask Robert to speak in his place. Robert and Gaby were privileged to hear from Ravel himself many comments as to how he wished his piano works to be performed, which they then passed on to their pupils.

Robert Casadesus recorded Ravel’s entire piano repertoire—see discography—and he became the champion of his Left Hand Concerto that many conductors never failed to ask him to perform on their programs.

From the beginning of his career, Robert loved to play Ravel’s solo piano works and, in 1924, he was the first pianist to give an all Ravel recital. After the performance, Ravel congratulated him and proposed to him to record on Eolian piano rolls in London a number of his works (actually those which were too difficult for him to play).

Not long after, Ravel and Robert joined forces throughout a tour of Spain, where they performed four hand pieces, then shared the rest of the program. Their friendship grew between concerts: long conversations on music, great composers, etc. Fairly frequent musical evenings hosted by mutual friends, then another kind of collaboration with the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. Ravel accepted the nomination of General Director there in 1934, and with Robert named Isidor Philipp’s successor as head of the piano department in 1935, that summer gave free rein to their collaboration.

Indirectly and through family connections, Robert had already entered the American world in 1921 when he became the assistant to Isidore Philipp, then professor at the American Conservatory of Fontainebleau. This Conservatory had been created jointly in 1921 by Francis Casadesus (the eldest of Robert’s uncles) and Walter Damrosch, conductor of the New-York Philharmonic.

The men had met in 1917, during the Great War, at the camp in Chaumont, where Francis was teaching harmony to American military bandleaders, helped by several French musicians (André Caplet, Jacques Pillois…). Walter Damrosch, who was quite enthusiastic about this teaching, had thought that it ought to be perpetuated for young Americans musicians, once the war was over. Thus began the long history that unites Robert and his family with the United States.

For the Casadesus family, the American Conservatory of Fontainebleau would play a preponderant role about which Robert had surely not dreamt in the early 1920s. As of the 1930s, Robert began an American career, which took him back every year to New York and everywhere else in that vast country, playing with the greatest: Toscanini, Koussevitzky, Rodzinsky, Mitropoulos, Walter…

Crossing the Atlantic no longer held any secrets for him, and he acquired a taste for the great French ocean liners that linked Le Havre and New York. A cigar-smoking gourmet, these voyages were, for Gaby and for him, moments of relaxation and shared happiness. The family had grown with the birth of two sons: Jean, in 1927, and Guy, in 1932. The boys went to school like any other children. Jean began the piano quite young, with Aunt Rosette, and he was to follow in his parents’ footsteps. As for Guy, he briefly took up the violin but paid little attention to it and later turned, without hesitation, to jazz piano as well as following a non-musical career.

Tours and years of exile in the United States

The foreign tours multiplied. Aside from England, the Netherlands, Germany and all the other countries of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East or South America, it was the United States of America that would be the fertile terrain of his career.

Robert Casadesus made his debut in the United States in 1935 and performed in New York. Toscanini was in the room and, full of admiration, invited him to play the following year under his direction, with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Success was immediate and this marked the start of many tours, especially in the United States, but also in some forty countries in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and Japan.

From 1936 on, Robert and Gaby toured the United States yearly including in January 1940. Fortunately, they took their two sons with them, as the situation in Europe was so worrisome. It was then that a return to France proved impossible, given the circumstances. Robert was asked, in April of 1940, to try to continue the American Conservatory in the United States that summer, a session at the Château de Fontainebleau being out of the question, and he and Gaby chose Newport, RI.

Robert and Gaby therefore decided to remain in the United States, never suspecting that their exile would last six years…Friends suggested that they rent a house in Princeton, New Jersey, so that the boys could have good schooling and sport activities.

In 1942, little Thérèse transformed the quartet into a quintet. Robert, happy to have a daughter, nicknamed her ‘la dauphine’ (or heiress apparent), and composed a cradlesong for her. Born in the United States, Thérèse would make her life there and marry an American. The six American years were a fascinating experience for them all. The family moved a number of times, thus living in several different houses. Robert and Gaby had to familiarise themselves with the English language, which, his whole life, Robert would speak with an accent à la Maurice Chevalier! They met fellow exiles, including Albert Einstein, their neighbor in Princeton. A great music lover (we know he played the violin quite respectably), he participated in friendly Mozart concerts with Gaby.

This long American stay would also see the birth of what would become the famous ‘Casadesus-Francescatti’ piano-violin duo, which would be influential throughout the world for many years.The hazards of exile brought together these two equally talented musicians. Zino Francescatti and his wife, Yolande, had also been obliged to remain in the United States, where they found themselves in 1939. In the summer of 1942 they became neighbors of the Casadesus clan, who were running the American Conservatory in Great Barrington, MA where Mrs. Francescatti taught solfège. Such good fortune! After beginning to play in the evenings for the pleasure of making music together, the duo decided to perform professionally. Concerts across the country followed, along with discs for Columbia (which became CBS and now Sony) and, after the war, international tours.

The duo continued up until Robert’s death. The two men got along famously, and one had to have seen their complicity in rehearsal, have felt their concentration during a concert, always in the shared love of music, to conclude that they were destined to meet. Amongst others, their recordings of the Beethoven violin sonatas bear living witness to that. The United States was also the continuation of the Fontainebleau School to which Gaby gave unsparingly of her energy and devotion.

She fought tooth and nail to surmount material difficulties, which were not lacking during the war years, America having, in turn, joined the fight and not paying particular attention to the logistics of a music school. But, for Gaby, it was a priority, and she let it be known, struggling to obtain the subsidies necessary for its operation.

Return to France et international career

After the war, the American Conservatory reopened in Fontainebleau for summer sessions. Robert was the first director of this resuscitated school, up until the return of Nadia Boulanger, also exiled in the United States during those dark years. This forced exile would become, in the memory, a slice of happy life, despite the distance from the rest of the family and the absence of news about what was really going on at home. During those long years, the Casadesus family got to know all the great musicians the New World had to offer, whether natives or fellow exiles. The intellectuals had, to a large degree, gathered around New York or on the West Coast. Amongst these personalities, they met Béla Bartók, who had fled Hungary. At the time, his music had little support from the American public, and, in 1945, he died in New York in near-total destitution, following a serious illness. Stravinsky was also there, as was Darius Milhaud, who, with his wife, Madeleine, became close friends. The young Leonard Bernstein was already drawing attention, and Horowitz, Toscanini’s son-in-law, reigned over the piano in New York.

Finally the Armistice was signed on 8th May 1945, and a year later the Casadesus family went home. Fontainebleau witnessed the rebirth of the American Conservatory, and Robert, Gaby and the children moved back into their Parisian flat in Rue Vaneau. They again found family and friends and readapted to living à la française. Nonetheless, in the euphoria of the homecoming, a painful event struck the family: little Thérèse contracted poliomyelitis from an American student at the summer session of the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau. Without changing their daily life or concert tours in any way, Gaby and Robert joined forces and fought at her side to help her regain her motivity. This struggle, conducted with tenacity and love, would eventually bear fruit. Every year, America welcomed Robert for concerts and recitals across the continent that he now knew so well. He continued to record exclusively for Columbia Records, which had become CBS, both in New York and Paris. Robert was also a dedicated Steinway artist (from the Thirties to the end of his life) and in 1968 was honored by the Steinway family in a special ceremony.

The conductors who accompanied him at the time included, amongst others…

Eugene Ormandy (1899-1985). From the 40s to the 60s, Robert performed quite frequently with the Philadelphia Orchestra Ormandy conducted for decades. They collaborated on the famous recording of Ravel’s Left Hand concerto—the photo shows Robert indicating some points of interpretation Ravel had wished. Ormandy’s predecessor, Leopold Stokowski, practically a Hollywood star but also a champion of contemporary music, conducted Robert’s 2nd Piano concerto (op. 37), with the composer at the piano.

Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960). He suggested to Robert to include his son Jean in rarely performed 3 piano repertoire (see The first family of the piano)—Bach, Mozart—with the New York Philharmonic.

Charles Munch (1891-1968). Succeeded Serge Koussevitsky to lead the Boston Symphony, and was partial to French music—d’Indy, Franck—so close to Robert’s heart. They enjoyed a perfect musical partnership.

George Szell (1897-1970). The famous conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra—considered the best in the US along with the Chicago Orchestra—shared a very close friendship with Robert until he died. Their musical entente in the Mozart concerti remains the gold standard.

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990). In partnership with the young Bernstein, who also loved French music, they performed and recorded with the New York Philharmonic, Saint-Saëns’ 4th concerto and the Fauré Ballade, emblematic works of the French repertoire.

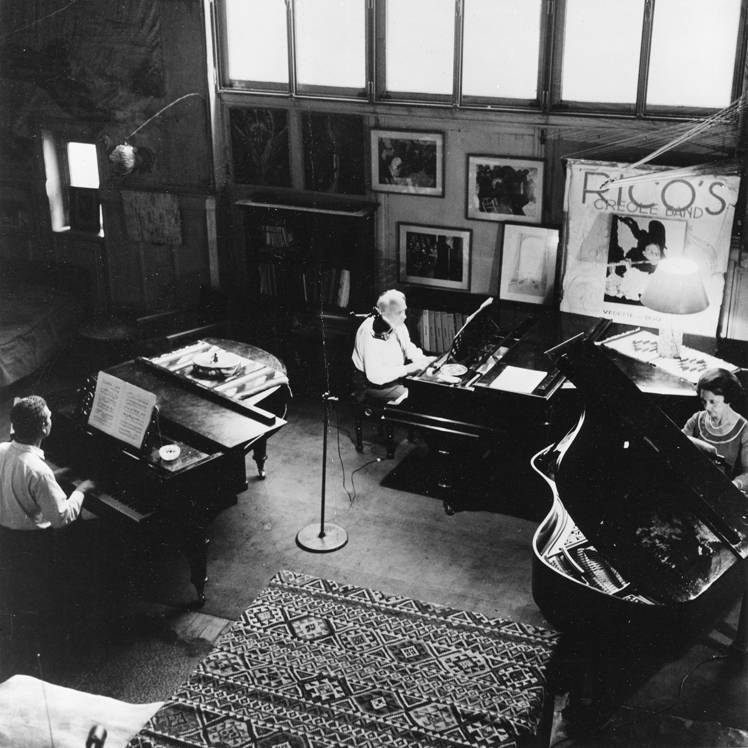

The First Family of the Piano (with Jean)

Every summer now, the European festivals welcomed Robert, Robert and Zino, or Robert, Gaby and Jean, for Jean had, in turn, embarked upon an international career. He divided his time between the United States and Paris, maintaining a home on either side of the Atlantic. He married Evie Girard, daughter of painter André Girard, who, with his family, had also spent the war in America. The Girards had numbered amongst the friends united by exile. With this marriage, the bonds became family. The three pianists lived their careers independently, but they enjoyed getting back together in front of two or three pianos to play Bach, Mozart or Robert Casadesus: Robert had, in fact, composed a concerto for three pianos in order to further knit, according to the expression of the Americans, ‘the first family of the piano’. This title was chosen for a televised documentary featuring the Casadesus trio produced by the Bell Telephone Hour in 1967. It was aired nationally and very popular at the time. It is still available in DVD from Video Artists International.

‘Family’ was a word that had a sacred sense for Robert. The family, which, during the summer, between two concerts elsewhere, gathered in the Recloses house, near Fontainebleau, and, during those rest breaks, the three pianos gave way to three bicycles that the three pianists readily mounted for long rides in the forest. Like any family, life brought the Casadesus family its share of joys and tribulations. The year 1972 was doubtless the most tragic: in January, Jean died in a motor accident. Poor weather conditions had prevented the plane that Jean was to have taken to give a concert in Canada from taking off. With another passenger, he decided to hire a car. The road was slippery; Jean was seated next to the driver…

Robert, affected in the deepest part of himself, never got over his grief. His health declined rapidly, and he was obliged to cancel a good number of concerts during the summer. On 19th September, he joined Jean. Gaby, devastated by this double ordeal, which affected her life as a wife and mother the same year, faced up to it with courage and decided to perpetuate her husband’s memory. Her charisma and tenacity enabled her to succeed fully.

Conclusion

Gaby Casadesus devoted more than twenty-five years to maintaining alive the memory of her husband, with major projects bearing his name and featuring some of his works–the Robert Casadesus International Piano Competition in Cleveland (1975-1993) then the Rencontres Internationales de Piano in Lille (1996-2005), and monitoring the activities of the Robert Casadesus Association. In the meantime, she managed to keep up with her professional endeavors as a performer and teacher recording some of Robert’s works, participating in many juries, teaching at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau and the Académie Ravel in St Jean-de-Luz. In 1988, Buchet-Chastel published her book of memoirs Mes Noces Musicales, relating the remarkable career of her husband and their duo, which will soon be available in English translation.

The composer Gréco Casadesus, Robert’s first cousin, pursued Gaby’s endeavors by publishing many of Robert’s hand-written scores and arranging to have them recorded, putting the final touch to the composer’s considerable output. At the beginning of the 21st century, Gréco and Robert’s son Guy created the first robertcasadesus.com website in 2005 to bring the famous pianist and composer Robert Casadesus, to life for today’s music lovers. You will now be able to peruse its updated version.

In 2022, the 50th anniversary of Robert Casadesus’ death will be memorialized. He was one of the greatest pianists of the mid-twentieth century, along with Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz; known in the United States as “a household name”. His memory is still very much alive today, as testified by the release in 2019 of a 60 CD box-set by SONY of his complete recordings for Columbia which also include a number of his works.

To better acquaint young musicians with Robert’s own music is being prioritized today by his heirs, under the guidance of his daughter Thérèse and his grandsons Carter and Ramsay Casadesus Rawson. Therese’s longtime involvement with the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau has allowed her to introduce several of his piano and chamber works to the students who come each summer to to the Chateau, where they learn and perfect French repertoire, listen to various recent interpretations, and view doctoral theses devoted to him in the last few years. The number of visits to the website testify to Robert Casadesus’ international reputation to this day, particularly in Japan, and we hope they will increase further with our updated site.

Text by Jacqueline Muller

and the Casadesus family.